Introduction

By reading this article, you won't only encounter vague keywords or directionless arrows. Instead, you'll get direct code snippets that you can implement in your project today. So, why wait? Scroll down!

A Glimpse into the Problem

My challenge was to design a livestream page with thousands of Concurrent Users (CCU). Here are some primary requirements:

- The system predominantly reads data at a near 99/1 ratio.

- The homepage's data is dynamic, customizable for each user.

- Frequently updated 'hot' data is managed by a background worker system.

The infrastructure for the livestream has already been optimized by another team, so my sole responsibility is to create a web page for users to access and engage with.

Architecture I'm Using

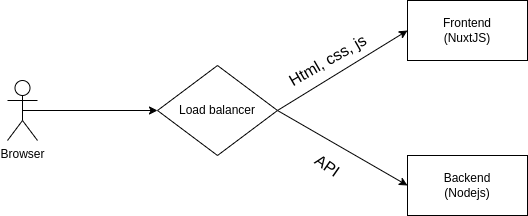

Currently, I'm operating with a basic monolith model. Of course, I've separated the frontend using NuxtJS and the backend API on Nodejs. This separation is a first step to ensure easy scalability without requiring intricate architectures like micro-services just yet.

This livestream page handles a lot of dynamic data. For swift development, compatibility across most devices, from laptops to mobiles and even embedded browsers, we still use the short-polling mechanism. There's a wealth of resources discussing other realtime data update techniques like long-polling, server-sent events, and websockets. However, nothing is as easy to implement and quick to produce as short-polling. The most crucial deciding factor for this product was its development speed.

On the frontend, the chosen framework is NuxtJS. The primary reason is that Vue (Nuxt's base) has an easy-to-understand and familiar syntax. I selected Nuxt to leverage Server-Side Rendering (SSR) right from the project's inception. With Nuxt, both SPA and SSR modes are available, offering flexibility for future additions.

On the backend, the web server I've opted for is Fastify. It's vital to understand when one should be concerned about overhead, rather than blindly following internet claims. If my team is still drowning in slow queries or latency measured in hundreds of milliseconds or even seconds, then there's no need to focus on framework overhead. However, if an API's time is measured in a few to tens of milliseconds, that's when framework overhead becomes crucial.

Framework overhead is a concept used to compare the processing capabilities of two frameworks. Essentially, it involves comparing two empty requests to see which one has a lower latency, and hence is faster. For instance, when comparing Fastify to Express, if Fastify has lower overhead, it's deemed faster.

The most important thing when making a performance-based decision is understanding the trade-offs. For instance, choosing Fastify means I'm potentially sacrificing many features that Express inherently provides, and there's the consideration of my team's familiarity with Fastify versus Express.

Of course, with a logical app architecture, changing web servers isn't a major issue, and can even be relatively simple. Let's take a look at my project's folder structure:

livestream-project

├── src

│ ├── index.ts

│ ├── index-worker.ts

│ ├── config

│ │ ├── environment.ts

│ │ └── errors.ts

│ ├── common

│ │ ├── auth

│ │ │ ├── auth.request.ts

│ │ │ ├── auth.response.ts

│ │ │ ├── auth.service.ts

│ │ │ ├── auth.transformer.ts

│ │ └── logger.ts

│ ├── api

│ │ ├── application.ts

│ │ ├── auth

│ │ │ ├── auth.controller.ts

│ │ │ ├── auth.middleware.ts

│ │ │ ├── auth.route.ts

│ │ │ └── auth.validator.ts

│ │ ├── response.middleware.ts

│ │ ├── router.ts

│ │ └── server.ts

│ └── worker

│ ├── application.ts

│ ├── router.ts

│ ├── server.ts

│ └── sync

│ └── sync-realtime-data.job.ts

├── package.json

└── yarn.lock

I've implemented a multiple-entrypoint structure to initiate different components of the project like api, worker, etc. Common logic is managed under common. The API directory contains web server-related logic such as Controller, router, validator, and not business logic. Therefore, switching the web server from the familiar Express to Fastify was relatively straightforward."

Basic Numbers at a Glance

Alright, before diving in, let's quickly look at some basic numbers related to the performance of our current system.

Starting with the most called API in our app, which fetches item details:

- Test machine specs: Core i5 4200H 4 cores, 12GB RAM + SSD

- Test environment: Local DB on docker, running a single node process

- Endpoint:

/items/:id

All the results in these tests are based on my actual running code and real data. This makes them significantly more complex than the sample code provided. However, all performance-related differences are reflected here.

async function getItemNoCache(req: FastifyRequest, res: FastifyReply): Promise<void> {

const { id } = req.params as { id: number };

// This fetches the item directly from the database

const item = await ItemService.getItemById(id);

return res.sendJson({

data: item.transform(),

});

}

To have comparable results and exclude network-related factors, I've added an empty endpoint that just returns the exact response of the /items/:id endpoint (this ensures all tested APIs have the same response size, eliminating network and data transfer differences).

async function getItemEmpty(req: FastifyRequest, res: FastifyReply): Promise<void> {

return res.sendJson({

// Mocking an item response

data: {

id: 10,

name: 'sampleItem',

attribute: 'sampleAttribute',

...

},

});

}

Testing results for 100k requests, with concurrency at 200 using the k6.io tool:

| No. | Test | Http time (s) | Http RPS | avg(ms) | min(ms) | max(ms) | p95(ms) | Node CPU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empty GET | 18.5 | 5396 | 36.95 | 0.91 | 140.66 | 53.47 | 115.00% |

| 2 | Get by id | 154.9 | 645 | 309.59 | 174.96 | 557.06 | 349.28 | 230.00% |

The Empty GET showcases the overhead of the framework and data, indicating the performance when the code is practically dormant, just responding with raw data.

Even though a single instance of my node is running at full CPU (100% indicates one full CPU core is used), some might wonder how Node.js, being single-threaded, sometimes uses 115% of CPU and even goes up to 230% (more than 2 CPU cores). Does this mean the long-standing notion of Node.js being single-threaded is misleading?

~> Not really misleading, just not the full story. The event-loop running our code is single-threaded. This means our code operations on the CPU are single-threaded. However, external I/O operations, specifically when working with libuv (a core library in Node handling asynchronous operations like file reading, http requests, DNS, etc.) are performed on a thread pool with a default of 4 threads. The thread count for libuv can be configured via the UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE environment variable.

I'm using a Postgres database with the node-postgres driver. Deep inside, this driver uses libpq, which in turn uses libuv. That's why, when calling the Get by id API, my node instance utilized 230% of the CPU.

A tricky question often posed to Node.js developers is: Can a single-instance Node application utilize more than one CPU?. Those who impulsively think of it as single-threaded and quickly answer no are mistaken.

Implementing the Cache-Aside Pattern with Redis

Directly querying the database isn't the best for performance. Based on my experience, 10 concurrent users generate 1 req/s. So, the figure of 645 req/s can only cater to 6k concurrent users under ideal conditions (limited database data and users only calling get item by id). To reach 10k concurrent users, it seems more resources would be needed.

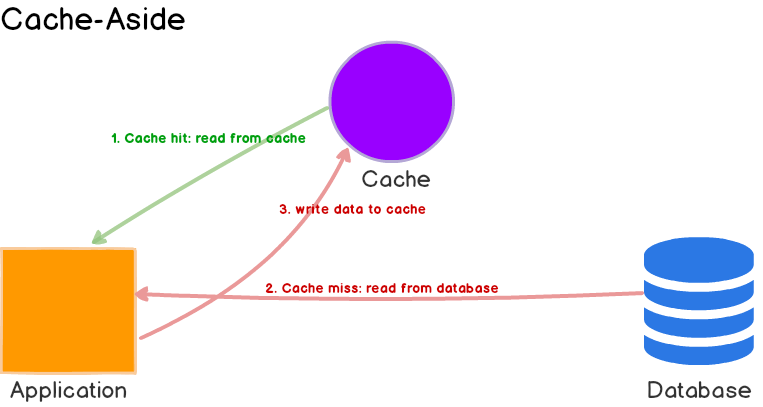

But now, I'll implement the most straightforward solution everyone uses – caching with Redis.

The simplest way to cache with Redis is using the cache-aside pattern. I've condensed the cache implementation into the following function:

async function getOrSet<T>(key: string, getData: () => Promise<T>, ttl: number): Promise<T> {

let value: T = (await redisClient.get(key)) as T;

if (value === null) {

value = await getData();

if (ttl > 0) {

await redisClient.set(key, value, 'EX', ttl);

} else {

await redisClient.set(key, value);

}

}

return value;

}

Subsequently, in my code, it's called as:

async function getItemFromRedis(req: FastifyRequest, res: FastifyReply): Promise<void> {

const { id } = req.params as { id: number };

const itemResponse = await redisAdapter.getOrSet<IItemResponse>(

`items:${id}`,

async () => {

// This fetches the item directly from the database

const item = await ItemService.getItemById(id);

return item.transform();

},

30,

);

return res.sendJson({

data: itemResponse,

});

}

All done, I've cached the item's response with a Time-to-live of 30 seconds. Let's continue testing the performance using k6.io:

| No. | Test | Http time (s) | Http RPS | avg(ms) | min(ms) | max(ms) | p95(ms) | Node CPU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empty GET | 18.5 | 5396 | 36.95 | 0.91 | 140.66 | 53.47 | 115.00% |

| 2 | Get by id | 154.9 | 645 | 309.59 | 174.96 | 557.06 | 349.28 | 230.00% |

| 3 | Cache Redis | 24.1 | 4143 | 48.14 | 10.86 | 195.4 | 68.19 | 125.00% |

Well, the speed seems pretty good, right? That's our first step done. We'll apply this caching mechanism to a few other APIs that fetch data from other pages, depending on the data changes at each place.

Short-polling and the public bandwidth issue

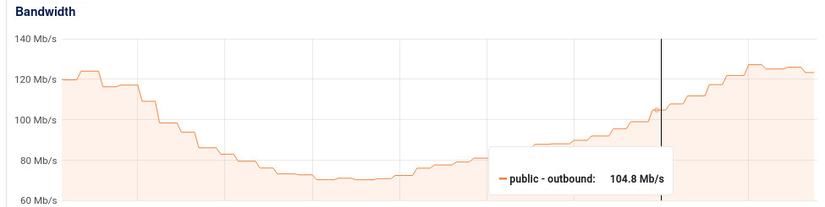

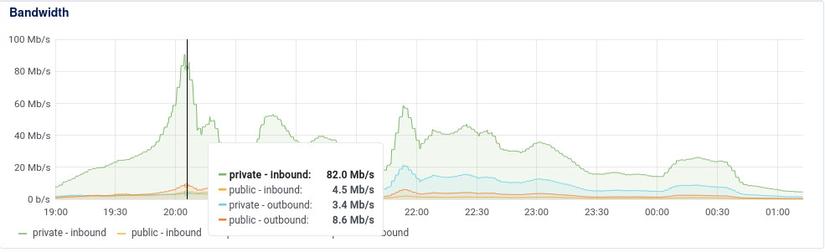

Things were going well until I noticed an issue when the CCU increased: our public output bandwidth shot up to hundreds of Mbps. Of course, for a regular website, a number close to 100Mbps isn't a big deal. But when you're targeting 10,000 CCU and only have 2-3k CCU, this bandwidth increase should be reconsidered. Especially after we shifted our application for users to use Nuxt CSR instead of SSR (which means almost all static assets are cached on the CDN and the HTML is extremely lightweight).

I quickly identified the issue: it was due to the short-polling mechanism we were using.

Choosing short-polling was quite suitable for our current problem and the resources allocated for this project.

Previously, Express helped me with default settings for using Etags to mark unchanged responses and return HTTP status 304 to help the client save bandwidth. Now, I had to do it manually with Fastify. Of course, it's not challenging, but you should be aware of the need to do it yourself.

import fastifyEtag from "@fastify/etag";

import fastify from "fastify";

const server = fastify();

await server.register(fastifyEtag, { weak: true });

After enabling Etag, I managed to reduce the public output bandwidth by ~4 times. This makes sense as our data changes about once a minute, and short-polling is set to 15 seconds.

For some specific list-type APIs, instead of refreshing the entire list, I further optimized by separating infrequently changed data from frequently changed data. This allowed me to create a separate API for frequently changed lists, further reducing the public output bandwidth.

With 3k CCU, my public output bandwidth is just above 10Mbps.

The power of promise and the Thundering Herds issue

Although I was quite satisfied with the system's short-term performance, I couldn't ignore some alarming signs when monitoring the database load and slow queries:

- Slow queries emerged when the database CPU usage spiked.

- Many identical slow queries appeared simultaneously.

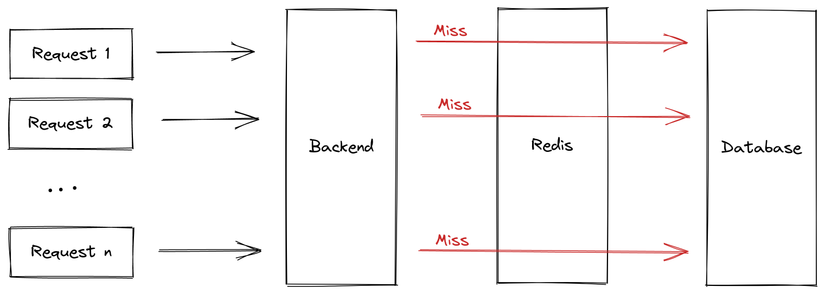

Okay, our system usually runs cron jobs to update large volumes of data from other systems. It's normal for the database to be heavily loaded during these times. Even if slow queries emerge during these peak times, it's acceptable. But, seeing many identical slow queries at the same moment indicates a potential system collapse.

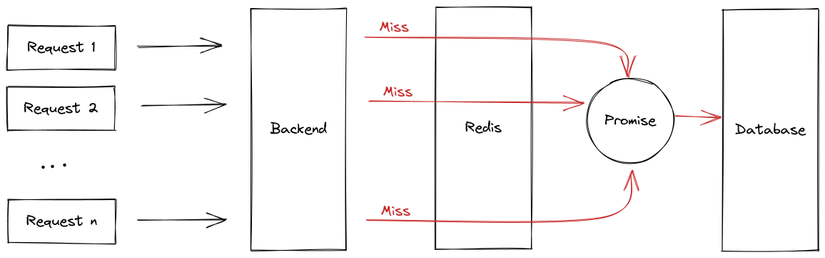

That's precisely the Thundering herds problem, also known as Cache stampede. It means the system cache continually misses because the previous request (to cache the result) isn't finished before the next one arrives. This sends requests directly to the database, overloading and potentially crashing the system.

To tackle this, when the first request misses the cache, I'll mark that the database call is underway, preventing subsequent requests from directly accessing the database. They will wait with the first request. Luckily, our Node.js is fundamentally single-threaded, so initiating and accessing global variables is straightforward without considering race-condition issues.

To lock the database call, I used the following code:

// Define a global map to store calling promise

const callingMaps: Map<string, Promise<unknown>> = new Map();

async function getOrSet<T>(key: string, getData: () => Promise<T>, ttl: number): Promise<T> {

let value: T = (await redisClient.get(key)) as T;

if (value === null) {

// Check if key is being processed in callingMaps

if (callingMaps.has(key)) {

return callingMaps.get(key) as Promise<T>;

}

try {

const promise = getData();

// Store key + promise in callingMaps

callingMaps.set(key, promise);

value = await promise;

} finally {

// Remove key from callingMaps when done

callingMaps.delete(key);

}

if (ttl > 0) {

await redisClient.set(key, value, 'EX', ttl);

} else {

await redisClient.set(key, value);

}

}

return value;

}Pay attention to the line const promise = getData();. It's not a mistake; we intentionally didn't use the await keyword before the getData call. The result from getData() will return a promise. We'll immediately store this promise with its associated key into a global Map named callingMaps. So, if another request comes in before the value = await promise; line completes, it will find the ongoing promise in callingMaps and wait for its result, preventing another database request.

By saving the promise when calling the database, we've eliminated unnecessary database requests during a Thundering Herd situation. So, even with 1000 simultaneous requests and a cache miss, only one request will access the database.

Caching promises is a powerful technique when used correctly. Just remember not to accidentally add await in front of

const promise = getData();, or everything goes haywire.

Memory Cache and Internal Bandwidth Issues

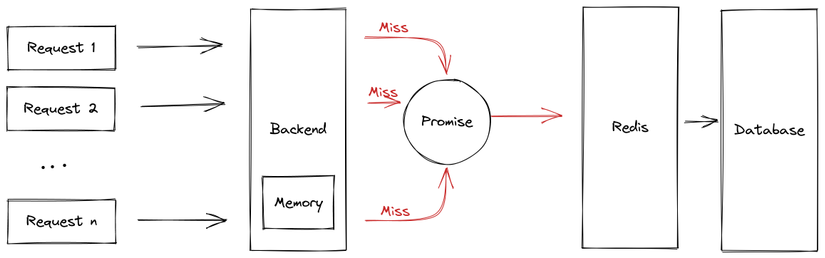

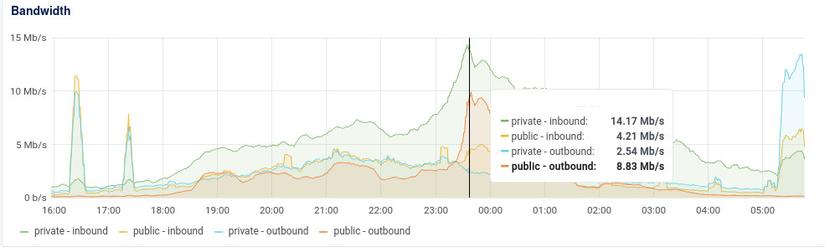

After addressing public bandwidth issues, we face internal bandwidth challenges. Though we've used promises to prevent Thundering Herds by saving the running promise, we quickly realized this isn't enough for a system with increasing Concurrent Users (CCU).

As shown in the image, our internal bandwidth is almost 10 times our public bandwidth. This is after optimizing our public bandwidth using Etags. So, our system still consumes internal bandwidth to fetch data from Redis, but if the response matches the Etag, no public bandwidth is consumed to send data to the client.

Having 100Mbps internal isn't significant, but after operating multiple systems on the cloud using Redis, we've encountered many situations where Redis bandwidth hits several hundred Mbps, resulting in considerable network waiting times. Moreover, cloud VPS internal networks don't come with specific commitments. Hence, using several hundred Mbps is risky.

So, how do we optimize internal bandwidth for an operating system? The solution is... to stop using it.

Switching entirely from Redis cache to Memory cache would solve the network issue. However, relying solely on Memory cache introduces other problems:

- Challenging cache invalidation

- Limited memory for one instance

- Cold cache upon service re-deployment

- Horizontal scaling reduces cache efficiency (low cache hit ratio)...

There are many more challenges with using Memory cache.

Why not use both? We can add another function to wrap the above getOrSet:

async function getOrSet<T>(key: string, getData: () => Promise<T>, ttl: number): Promise<T> {

let value: T = (await redisClient.get(key)) as T;

if (value === null) {

value = await getData();

if (ttl > 0) {

await redisClient.set(key, value, 'EX', ttl);

} else {

await redisClient.set(key, value);

}

}

return value;

}

const burstCache = new NodeCache({

useClones: false,

});

async function burstGetOrSet<T>(key: string, getData: () => Promise<T>, ttl: number, burstTtl: number): Promise<T> {

if (burstTtl === 0) {

return getOrSet<T>(key, getData, ttl);

}

let value = burstCache.get<Promise<T>>(key);

if (value === undefined) {

value = getOrSet<T>(key, getData, ttl);

burstCache.set(key, value, burstTtl);

}

return value;

}

We'll skip the callingMaps mechanism from the previous section. Note that when we call getOrSet, we intentionally do not use await, so the result returns as a promise.

We're using a popular Node memory caching library called node-cache. Notice that when initializing, we use the option useClones: false to prevent node-cache from cloning our promise. This approach saves memory and reuses the original promise from the first request.

When applied, it's straightforward; we just add one more parameter called burstTtl, which represents memory caching time.

async function getOrSet<T>(key: string, getData: () => Promise<T>, ttl: number): Promise<T> {

let value: T = (await redisClient.get(key)) as T;

if (value === null) {

value = await getData();

if (ttl > 0) {

await redisClient.set(key, value, 'EX', ttl);

} else {

await redisClient.set(key, value);

}

}

return value;

}

const burstCache = new NodeCache({

useClones: false,

});

async function burstGetOrSet<T>(key: string, getData: () => Promise<T>, ttl: number, burstTtl: number): Promise<T> {

if (burstTtl === 0) {

return getOrSet<T>(key, getData, ttl);

}

let value = burstCache.get<Promise<T>>(key);

if (value === undefined) {

value = getOrSet<T>(key, getData, ttl);

burstCache.set(key, value, burstTtl);

}

return value;

}

This time will be shorter than the ttl time which is the redis cache time. burstTtl is usually only set for a few seconds, that is, just to avoid making many repeated calls to redis at times of high requests. Therefore, it will almost retain the properties of the Redis cache system such as accepting invalidates with a delay of a few seconds, the amount of memory used by the instance is relatively small,...

After testing performance with k6.io:

| No. | Test | Http time (s) | Http RPS | avg(ms) | min(ms) | max(ms) | p95(ms) | Node CPU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Empty GET | 18.5 | 5396 | 36.95 | 0.91 | 140.66 | 53.47 | 115.00% |

| 2 | Get by id | 154.9 | 645 | 309.59 | 174.96 | 557.06 | 349.28 | 230.00% |

| 3 | Cache Redis | 24.1 | 4143 | 48.14 | 10.86 | 195.4 | 68.19 | 125.00% |

| 4 | Cache Mem (burst) | 22.1 | 4516 | 44.16 | 2.92 | 176.58 | 59.81 | 120.00% |

As you can see, using memory cache in our system isn't about solving a speed problem. Benchmark results show that memory caching outperforms Redis caching by only about 10% in performance. This approach keeps the data and code characteristics while reducing internal bandwidth by 5-6 times.

With this method, we can push the CCU to 10k or even 100k, if you have the MONEY 🤣.

Conclusion

From this article, I've learned three things:

- Optimization is the harmonious balance of increasing output with the most reasonable input costs.

- The real challenge is enhancing output with a reasonable trade-off, not just seeking the highest results.

- Caching remains easy, how to combine cache types to suit a specific problem is difficult

0 Comments